I think everybody wanted to get into the war in one way or another. It was just a vast feeling. —Judge Debevoise

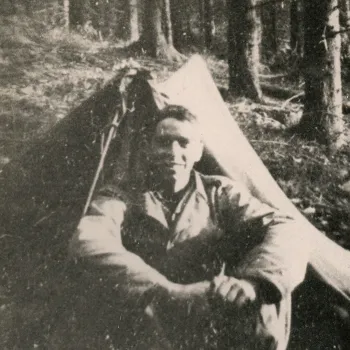

In this audio interview, U.S. District Judge Dickinson R. Debevoise of the District of New Jersey recounts his World War II combat experience and subsequent judicial career. Judge Debeboise, who sits in Newark, N.J., served in the U.S. Army from 1943-1945, retiring as a sergeant.

WWII Highlights:

- Landed on Normandy on June 7, 1944, the day after D-Day, with a combat engineering division.

- Cleared mines and roads, and built bridges fording Seine and Rohr rivers.

- Served in Hurtgen Forest campaign.

Transcript

Q. Tell me about your decision to enlist.

I think everybody wanted to get into the war in one way or another. Not everybody, but it was just a vast feeling. Originally I thought I’d like to be in the Navy, but my eyesight was too bad so I took the Army instead. You just had to go into something. And so that’s what I decided to do.

Q. When you joined the army, what were your first impressions?

A. Well, my first impression was just, I was notified to report to Fort Dix, NJ, where there a great many other young people being called from colleges and high schools. And the impression was of course there was a new and strange existence. We were sent by train to Georgia, where we were assigned to a battalion with which I spent the next two and a half years, the 294th Combat Engineer Battalion. Well, the invasion was coming, we all knew, and we were training for it. My battalion was sent to a marshalling area in Wales, where we were prisoners in prisons, virtually, for maybe two or three weeks preparing to be put on ships.

We were loaded in two sections. We had the advance section, and then the heavy equipment was going to come later. The advance section was taken by railroad to Bristol. We boarded the ship the Santa Pola, which by then was known as the Susan B. Anthony. It was a Grace (??) liner. We were then put on the ship, and it was there that we were told that the actual invasion was about to take place, and that we were going to land on D-plus-One in support of the 82nd Airborne Division, which was landing, of course, the night before by being dropped from the transport planes.

So we were on the ship sailing along the coast of Southern England on D-Day as the landings were taking place. We were prepared to disembark from the Susan B. Anthony. … We were to have done that. Actually we were preparing for that in the bottom hold of the ship when the ship hit a mine and started to sink. Therefore, we struggled to get from the bottom hold to the top hold, and up to the deck, which was a long process because there were lines of people in front of us. We were able to get out onto the deck, where the skipper of the ship was guiding us where to stand, and guiding whole batches of soldiers from one side of the ship to the other, in an attempt to balance it. The ship eventually went down after we’d all gotten off.

Q. What were your battalion’s duties in the early campaign?

A. Well, the early campaign was clearing roads, building bridges across rivers where the bridges had been blown, ferrying the 82nd Airborne troops across some of these small rivers. And then subsequently after that had taken place, we moved north toward Cherbourg, clearing the roads of the ruined towns of Balone, Montebourg, and on to Cherbourg. We also had to blow up mines and other explosives that had been left by the Germans. That was part of the road clearing.

Q. Did your engineering role take you into combat situations?

A. Yes, it did. Until Cherbourg was captured, we did mostly road work, searching for mines and building bridges. And the breakthrough from Normandy, I think that was in July, we were attached to the infantry, and we swept for mines as the infantry advanced … we were sweeping for mines and the battle was going on around us. The infantry was advancing, and we advanced along with it. This was before the final breakout from Normandy into central France.

Q. Can you tell me the circumstances around your Bronze Star?

Well, I think it was the crossing of the Rohr River, where I mentioned before, it was a turbulent river, and we had planes coming in and bombing us. They would drop flares and light up the whole bridge-site area and then drop bombs. I was taking my squad across the river in the middle of the night to work on the other side, actually to pull the anchor cable up to the far shore so that we could attach the floating boats on the pontoon bridge to it.

We were dive-bombed by one of the planes and my squad scattered. I got them back together again and we got across the river and finished the job of getting the anchor cable attached so the work on the bridge could continue. I think that may have been the specific episode that triggered the Bronze Star.

Q. You’ve kept up an active workload as a judge. For those who don’t have a lifetime appointment, what is that keeps you judging at this time of your life?

A. Well, I respect the court, and I’m interested in what I’m doing, what I have been doing over the years, so I’d like to continue doing as much of that as I’m physically capable of. Well, it’s partly just the satisfaction of doing this kind of work. If I didn’t like it, I wouldn’t have stayed on as long as I did, because I could have retired or gone elsewhere many years ago. This is just what I like to do most.

Q. Looking at your entire history, is there anything you are most proud of?

A. I would say the thing I’m most proud of is starting the Newark Legal Services project. This was part of my civil rights activity, and this was an organization under President Johnson’s Anti-Poverty Act, which continues on to today, providing indigent persons legal services. It was involved in the Newark riots back in 1967. They were attorneys in the housing case that I mentioned. So I would say that is probably the most constructive thing that I have done.

Q. Do you like the phrase “the Greatest Generation”?

A. I don’t like it. I think it glosses over the imperfections of the American society in that time. They forget that we were terribly racially biased in the Army. Black troops were treated miserably. … This is part of the Greatest Generation that isn’t mentioned, and I’ve seen terrible things that the military did. That inevitably will happen. I think it’s overblowing the character of the people who were in the Army, were in the Navy, in the Air Force. Which is not to diminish what they did, or in any way detract from their contributions, but I think to blow up any particular generation as the Greatest Generation is a mistake.

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.