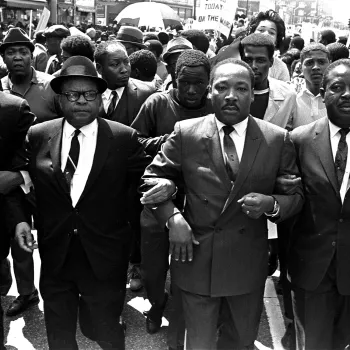

It was a rare, painful failure in Martin Luther King, Jr.,’s storied career of nonviolent protest. During a hastily organized march of striking sanitation workers, young protesters in the rear turned picket signs into weapons, smashing out storefront windows.

Stung, King vowed he would return soon to Memphis, Tennessee, to lead a second, more orderly march. City leaders, shaken by several days of looting and arson fires that followed, didn’t want King back.

The events of March 28, 1968, began the final week of Martin Luther King, Jr.,’s life. They also sparked a legal battle eclipsed by history—a federal court dispute in which King one last time defended the rights of aggrieved citizens to gather and march peacefully.

A program hosted by the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Tennessee earlier this month revisited that case, which began before but ended after King’s assassination. Panels featured lawyers from both sides of the dispute, as well as civil rights leader and former UN Ambassador Andrew Young.

Panel discussion during the program hosted by the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Tennessee. From left to right: Judge Bernice B. Donald, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and moderator; and lawyers Walter L. Bailey, Jr., W.J. Michael Cody, Charles F. Newman, and Frierson Graves, Sr.

District Judge John T. Fowlkes, Jr., said the program underscored the importance of courts and the law even in turbulent times.

“All these events, the march, the riots, the walkouts, overshadowed this backdrop of what’s happening in court, and the legal back and forth,” he said. “But the courts, whether state or federal, were very important to the civil rights movement, giving it legitimacy and legality.”

King’s Return

When King came to Memphis to support the sanitation workers, he had moved beyond his initial civil rights agenda. King sparked controversy, even among allies, by protesting the Vietnam War and planning a Poor People’s Campaign to focus on economic inequity.

Walter L. Bailey, Jr., whose law firm worked with the NAACP, took part in the March 28 demonstration that spun out of control. He met with King later that evening.

“He was a very unassuming, demure kind of person,” Bailey recalled, “but he was a strong advocate for his beliefs. He pledged he would return and demonstrate to the world, under the principles of Gandhi, that he could have a nonviolent peaceful demonstration.”

But tensions remained high in Memphis. The city was kept under curfew over the weekend, and national guardsmen were brought in as looting and fires flared. Mayor Henry Loeb called for martial law.

Frierson Graves, a Memphis lawyer who worked part time on the city attorney’s staff, was asked to research a legal strategy to prevent a second march. “I said that the only court civil rights leaders would respect is the federal court,” Frierson said. “If it went to state court, they would ignore any injunction, since those were the laws they were protesting. The only relief they had gotten was from the federal courts.”

To get into federal court, the city cited “diversity of citizenship,” based on the fact that King and other march leaders were coming from other states. On April 3, city lawyers asked Judge Bailey Brown for a temporary restraining order, with a goal of ordering a permanent injunction against a second march.

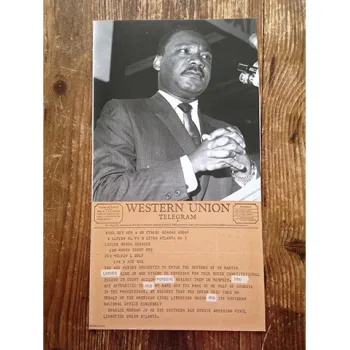

Partnering with Bailey’s law firm to defend King was Lucius Burch, a lawyer who was summoned into the case by a telegram from the American Civil Liberties Union. At 3 p.m. on April 3, the lawyers met in King’s cramped room at the Lorraine Motel.

“On one bed sat the lawyers. On the other twin bed was Dr. King, Jesse Jackson and Andy Young,” said lawyer and panelist W.J. Michael Cody. “There were five of them and six of us, sort of knee-to-knee.”

It was decided that Young should testify at the next day’s court hearing. King, worried that the previous week’s violence would undermine future protest campaigns, would not attend the hearing.

“King was very depressed. He had never had this happen to him,” Cody said.

‘Like a Pressure Cooker’

On April 4, the city alleged that King and other march organizers could not control unruly demonstrators. According to a transcript, available on the court’s website, public safety director Frank C. Hollomon testified that a second march posed “a clear and present danger,” threatening the entire city, the marchers, and even King himself.

King’s lawyers countered that the demonstration was protected by the First Amendment. They also said federal courts had established that marches could be permitted if conditions were set to maintain safety.

“We had strong law, strong facts, and a legendary client. We had eloquent witnesses and a fine judge in Bailey Brown,” lawyer Charles F. Newman said. “I don’t think the legal issue was ever in doubt. The issue was whether the chance of disorder was greater if the march was stopped or if it took place.”

Burch pressed that point, asking city witnesses whether it was better if a march were led by King, or occurred without him. They conceded that King’s presence would likely make the march safer.

Judge Bernice B. Donald, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit; James Lawson, a prominent Memphis civil rights leader, and a former sanitation worker from Memphis talk after the federal court event in Memphis.

Young testified that King’s organization was skilled at managing marches, and would agree to safety conditions. He also said the right to protest was essential to democracy, and public peace.

“The nonviolent movement has traditionally used marches as a healthy escape,” Young testified. “If there is no channel, … then it is sort of like a pressure cooker. It explodes somewhere.”

After the hearing, Brown told lawyers he would permit a second march, and directed lawyers to draft an order with safety conditions, which he would sign the next day.

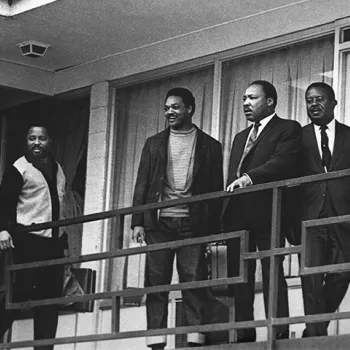

Cody said a member of the legal team found King at his hotel about 5:45 p.m. and let him know that the city’s injunction had been rejected. Fifteen minutes later, King stepped out onto his motel balcony. He was killed at 6:01 p.m.

Bailey was in his law library when he received news of King’s death. “When Dr. King was shot, I cried,” he said. “It was a huge honor and privilege to be a part of his legal team.”

On April 5, Judge Brown signed an order permitting the march. Three days later, Coretta Scott King led thousands of grieving marchers through Memphis. In keeping with Brown’s order, they walked in rows of six, guided by marshals with walkie-talkies. There was no violence.

Fifty years later, lawyers on both sides said the legal system worked. In a time of strife, the court calmly balanced civil rights and public safety.

“We had handled lots of civil rights cases, but we’d never had Dr. King as a client,” Cody said. “Everyone had legitimate positions, and I think the court in a businesslike way let those issues play out. At the end of the day, everyone in the courtroom felt it was the only appropriate decision—put tight restrictions on the march and let it take place.”

“The most memorable part of the hearing for me was how Judge Brown handled it,” said Graves, who represented the city. When the lawyers left the court at 5 p.m. on April 4, “I thought it was a routine-type lawsuit. We came to a good solution that would have worked. I didn’t think there was anything out of the ordinary, until an hour later.”

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.