Judge Dorothy Wright Nelson was a legal pioneer long before 1979, when she joined a historic class of women judges who reshaped the federal Judiciary, and she already had an uncanny knack for finding justice in non-confrontive ways.

During the late 1960s, Nelson was the nation’s only female dean of a major American law school. When the Los Angeles police chief branded her a communist during a time of student protests, she invited him to meet and talk over dinner. They became friends.

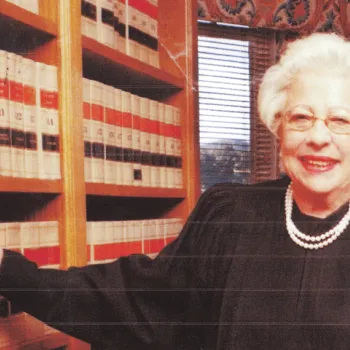

Judge Dorothy Wright Nelson. Photo courtesy of Judge Nelson.

But Nelson, a judge on the Ninth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, also could stand her ground on principle. She insisted that law school meetings, dinners and other events not be held in all-male clubs.

Nelson’s interest in the law got a boost in high school, when she played the role of a juvenile judge during a career day. “I enjoyed it. I felt I had the power to make things better,” she said. “I wanted to do what was right. To make decisions that were right and were fair.”

One of few female students at UCLA Law School, Nelson advocated diversifying the student body after she became a law professor at the University of Southern California. Nelson’s commitment was strengthened by her conversion to the Bahá'í religion, which emphasizes human equality.

“I began speaking up about recruiting more women and more minorities,” Nelson said. “I went to beauty parlors, talking with mothers about having their children—man or woman—come to law school.”

At USC, Nelson learned that human touches can make organizations work more smoothly—a lesson she later took with her to the Ninth Circuit.

As dean, she hosted faculty dinners at her home, thawing early resistance to Nelson from some professors’ wives. After noticing a high divorce rate among law students, Nelson invited students’ spouses to audit law school classes, so they could better understand the experience. Several wives of law students enrolled and became lawyers themselves.

Read the Series

This is the seventh in a series of articles about 23 women judges who in 1979 reshaped the federal Judiciary.

In turn, as more women enrolled, there was more collaboration. “Sharing of notes increased exponentially,” she said. “It changed the atmosphere of the law school.”

Nelson played a key role in the historic class of 1979 women judges. As USC dean and chair of the American Judicature Society, she was asked to help organize nominating commissions to vet judicial candidates for the federal appellate court.

One of Nelson’s proudest achievements as a judge was to increase the role of alternative dispute resolution in appellate courts, a tool previously associated with district courts. The innovation enabled parties to settle appellate cases before judicial panels ruled.

“Eighty-five percent of cases could be mediated,” said Nelson, who said traditional litigation costs needless time and money. “Wanting to bring people together, in a collaborative, unifying system, I find there are a lot of people open to that.”

1979: The Year Women Changed the Judiciary

The number of women serving as federal judges more than doubled in 1979. In this series, learn more about the trailblazers who reshaped the Judiciary.

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.