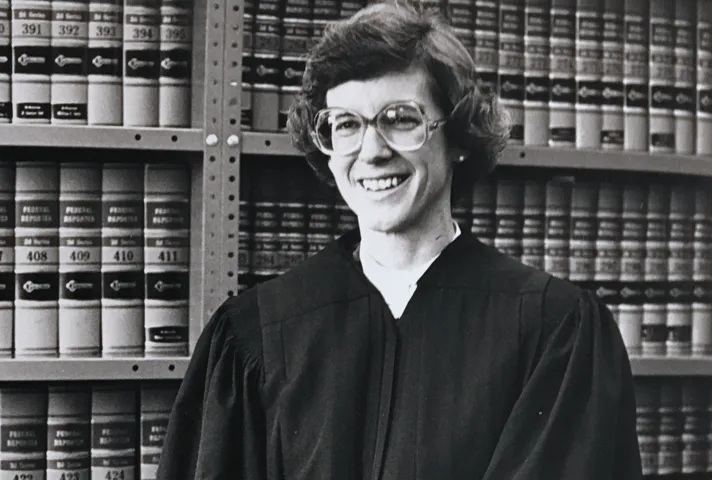

U.S. District Judge Barbara Crabb, shown after her confirmation in 1979, had prior hands-on bench experience as a federal magistrate (a position now known as magistrate judge). Photo courtesy of Judge Crabb.

District Judge Barbara Brandriff Crabb, of the Western District of Wisconsin, had a potential head start on a legal career. Her uncle, father, and grandfather all had law degrees, and as a child, “my parents taught me I could be anything I wanted to be.”

That said, like many women who came of age in the late 1950s and early ’60s, Crabb wasn’t committed to a full-time career, even after she enrolled at the University of Wisconsin Law School.

Judge Barbara Crabb. Photo courtesy of Judge Crabb.

“In college, it was sort of taken for granted that women would get married and have children,” Crabb said. “I did take time off when my children were little. I did all the things women were doing at the time.”

A compromise between work and family put Crabb on the path to her appointment as a federal judge—joining a historic class of women judges who in 1979 reshaped the federal Judiciary.

In 1971, while Crabb was working as a legal researcher, U.S. District Judge James E. Doyle invited her to apply for a new position as magistrate (now known as magistrate judge).

The job was half-time, and college students provided child care during her regular work hours. But unexpected requests to hurry back to the courthouse could cause disarray if no one happened to be on hand. “I would ask, ‘What do I do with my children,’ ” Crabb said.

More importantly for her career, Crabb gained hands-on bench experience. “Cases were piling up in huge amounts, and Judge Doyle didn’t begin to have the staff to take care of them,” she recalled. “He just needed a lot of help in a lot of different ways.”

At the same time, Crabb was inspired by Doyle’s caring and intelligence. As Crabb began to put order to the docket, her passion for a legal career quickly deepened.

“It was a very lively, exciting place to work,” Crabb said. “The kinds of cases people were bringing at that time were very challenging on every level.”

In January 1976, Crabb felt the harsh glare of publicity in a case involving a fatal 1970 bombing of a research building at the University of Wisconsin. The defense lawyer asked for bail, with a provision that the defendant be released to the care of a local family.

Read the Series

This is the eighth in a series of articles about 23 women judges who in 1979 reshaped the federal Judiciary.

Crabb granted the request.

“My first thought was, ‘Are you kidding? You’ve been avoiding arrest for more than five years, and now you want bail?’ ” Crabb recalled. “My second thought was that the family had a well thought out plan. The decision drew intense criticism at the outset, but it was soon forgotten, and the defendant met every condition of his release.”

When a 1978 law created a new district judgeship in Madison, Judge Doyle urged Crabb to apply. “He said he thought I would do a good job,” she said. “I just loved it. I loved the work.”

Looking back to 1979, she said the Judiciary’s evolution has been “remarkable.”

“It’s good for all of us,” Crabb said. “Greater diversity produces judges with a greater with a variety of life experiences and different ways of looking at the world and its problems.”

1979: The Year Women Changed the Judiciary

The number of women serving as federal judges more than doubled in 1979. In this series, learn more about the trailblazers who reshaped the Judiciary.

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.