Michael Gans had recently joined the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals in 1983, as a deputy clerk of court, when a crisis threatened to reduce the court’s paper records to mush.

Tipped off that water was pouring out of his courthouse in St. Louis, Gans raced back to the building, only to watch helplessly as safety sprinklers kept soaking the clerk’s office long after a small fire was extinguished.

“The sprinklers ran for about five hours because they couldn't find the shutoff valve,” recalled Gans. “All these paper files and docket sheets were under the sprinkler heads. We had to have everything freeze dried to try to save things.”

Since that long-ago episode, almost everything about how appellate courts manage their records and administrative staff is different, and Gans is one of several longstanding clerks of court to have witnessed the transformation firsthand.

“How we work has changed so dramatically,” said Gans. “I often say that if you could bring someone from the clerk’s office in 1920 into the same office in 1985, they would be able to sit down and do the job. But somebody who worked here in 2000 would not be able to do the work today.”

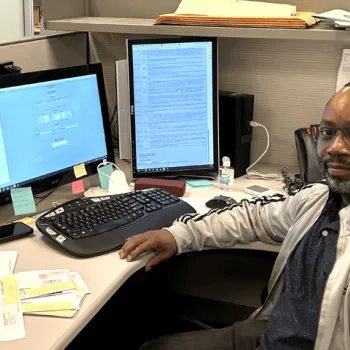

Gans was promoted to clerk of court in August 1991, and with 32 years of service, he is the nation’s longest-tenured clerk of court for a federal court of appeals. His observations are echoed by peers in other appellate courts who joined the Judiciary in the early 1980s.

“I came along at a time when there was a seismic shift beginning in clerk’s offices,” said Deborah Hunt, Sixth Circuit clerk of court. “It was starting to professionalize.”

While methods have evolved, the clerks’ essential mission remains largely the same.

“I sort of see myself as the person who has to know where everything is at any time and what everyone does,” said Mark Langer, who joined the D.C. Circuit in 1984 and has been clerk of court since 1995. “I have to know where things stand.”

Mark Langer, of the D.C. Circuit, has provided documentation for several Supreme Court nominations.

The federal law governing appellate clerks of courts was passed in 1948. However, such positions have existed since 1891, when Congress established the modern appellate system.

The federal Judiciary has 13 courts of appeals. Unlike district courts, which hear trials and testimony, appellate courts review lower-court decisions to make sure proceedings were fair and the law was applied correctly.

Clerks of appellate courts are both managers and lawyers. In addition to maintaining records and managing administrative staff, they make legal decisions on many procedural matters. In the D.C. Circuit, Langer oversees a team of staff attorneys who assess legal filings.

“We actually call it the legal division of the clerk’s office,” Langer said. “I read most of the work that the staff attorneys send to the court. If I have questions, I'll call them and say, ‘Did you think about this?’”

Most filings are routine, but emergency motions, such as for a stay in a death penalty case, can require attention at all hours.

“High-profile cases and emergencies are so stressful,” Hunt said. “During COVID, it seemed like everyone had an emergency on Friday night, where if this doesn’t happen by Monday, the world will come to a screeching halt. It wasn’t just our court, it was every court.”

All three clerks agree on the two greatest changes they have seen since the early 1980s. Information technology has eliminated most paper, and clerk’s offices manage their own budgets and operations. In earlier eras, even many small expenditures required approval by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts (AO).

In a 1984 photo in the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, employees were entirely reliant on typewriters and paper documents.

“When I became clerk, I saw a slew of letters between my predecessor and the AO over a typewriter repair,” Gans recalled. “They finally agreed to spend $30 to repair this typewriter. And I wondered, what did that deputy clerk do for six weeks while they hashed out this $30 bill?”

Hunt, based in Cincinnati, has been Sixth Circuit clerk of court since 2012. She also was clerk of a district court and bankruptcy court. Technology has revolutionized efficiency, but at her bankruptcy court, job attrition was painful.

“I was literally reducing staff every year,” Hunt said. “That’s the most disheartening thing to have to do.”

Each appellate court has its own history and culture. In the District of Columbia, Langer has served many judges who later joined the Supreme Court. His office has supplied extensive documentation for each confirmation process.

“It’s both exciting and stressful,” Langer said. “It’s all hands on deck because so much information needs to be turned over to the White House and Senate. But you feel like you’re a little part of history when that happens.”

The Eighth Circuit has been marked by continuity. Gans is just the fifth clerk of court in its 130-year history. And after 32 years, Gans still enjoys coming to work.

“I still love the work and I love the people,” Gans said. “I’ve had many wonderful friends here, and we’ve always had a sense of family and team. Being able to provide a service not just to the court but also to the public, it really is important to me.”

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.