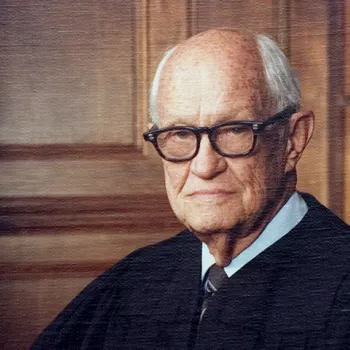

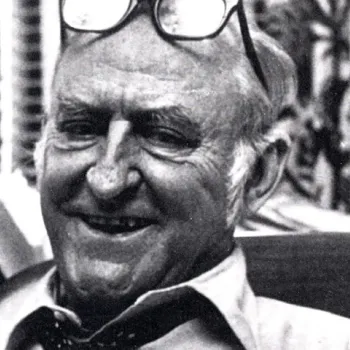

The memories of three legendary federal judges, who overcame deep-seated southern resistance to end segregation for millions of African Americans, were honored recently when the courthouses named after them were declared national historic landmarks.

The National Park Service granted landmark status to the Elbert P. Tuttle U.S. Court of Appeals Building in Atlanta; the John Minor Wisdom U.S. Court of Appeals Building in New Orleans; and the Frank M. Johnson Jr. Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse in Montgomery, Alabama.

In a July 20 ceremony in Montgomery, National Park Service Director Jerome Jarvis cited the judges’ roles in the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott, the 1961 Freedom Rides, the 1965 Selma to Montgomery March, and the desegregation of southern schools and universities. The judges also played leading roles in ending segregation of public facilities and upholding voting rights for African Americans.

“The courthouses in Alabama here, Georgia, and Louisiana were all involved in nation-changing events,” Jarvis said. “These courts bore the burden of enforcing Brown v. Board of Education after the Supreme Court rendered its historic decisions. …[They] dealt effectively with southern massive resistance and obstructionism.”

Gerald B. Tjoflat, a U.S. Court of Appeals judge for the Eleventh Circuit, who knew and served with all three judges, said they also were remarkable examples of courage, dignity and personal civility in the midst of a national storm.

“It was a wrenching time. People were afraid of the unknown,” Tjoflat recalled. “You had to have a good spine. They just took the high road, and remained gracious all the time.”

Judges Tuttle, Wisdom and Johnson, appointed in the 1950s by President Eisenhower, all received the Presidential Medal of Freedom before their deaths in the 1990s.

President Carter, honoring Tuttle in 1981, called him “a true judicial hero,” adding, “With steadfast courage and a deep love and understanding of the region, he has helped to make the Constitutional principle of equal protection a reality of American life.”

Honoring Wisdom in 1993, President Clinton cited the “clarity and reason” of his judicial writing, adding, “Judge Wisdom’s opinions advanced civil rights and economic justice.”

Two years later, Clinton said that Johnson, a U.S. district judge for the Middle District of Alabama, “changed the face of the South. … He challenged America to move closer to the ideals upon which it is founded.”

Wisdom, Tuttle and two other judges—John Robert Brown and Richard T. Rives—were known as the “Fifth Circuit Four.” Ironically, the term was coined as an insult by a fellow Fifth Circuit judge, Benjamin Cameron, who accused his colleagues of panel rigging in their zeal to overturn segregation.

By the time Tuttle became the Fifth Circuit’s chief judge in 1960, the promise of Brown v. Board had stalled, as school systems across the South ignored the Supreme Court’s mandate to integrate. The Fifth Circuit encompassed six southern states—Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and Florida—although the latter three became the Eleventh Circuit in 1981.

When some federal judges bottled up desegregation suits by declining to issue final rulings, the Fifth Circuit cut through the delays—demanding immediate desegregation without waiting for final lower-court action. Most dramatically, the Fifth Circuit ordered an openly defiant governor to desegregate the University of Mississippi—a decision that sparked rioting and required troops to restore order.

Grudgingly, after multiple legal challenges, the Universities of Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi all opened their doors to African Americans, and public school districts eventually did the same.

At the recent ceremony in Montgomery, Chief Judge Ed Carnes, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, said the judges were just as unyielding with other racial injustice. Wisdom, he noted, dismissed claims that one city’s “colored only” signs were voluntary as “a disingenuous quibble that must rest on the assumption that federal judges are more naive than ordinary men.” Carnes added, “The judges of the old Fifth were not naive.”

Although a district judge, Johnson is perhaps best remembered, largely because he crossed paths with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. In 1956, Johnson declared segregated buses in Montgomery were unconstitutional, ending a yearlong boycott that began with Rosa Parks’ arrest. In 1965, Johnson permitted marchers led by King to complete their journey from Selma into Montgomery, after police violence had thwarted them.

“There sat in this courtroom one person who refused to be a bystander, who spoke out against the status quo,” said Senior U.S. District Judge Myron H. Thompson at the July 20 ceremony. “Judge Frank Johnson, for me, stands as a symbol that goodness … in the hands of even just one person can overcome.”

Despite their monumental impact, the judges were described as personally modest.

In 1994, when the Court of Appeals in New Orleans was named after Wisdom, U.S. District Judge Martin L.C. Feldman said Wisdom’s “noble humility in the face of his vast accomplishments seems an almost inhuman feat.” But Wisdom also had a playful side, Feldman noted, including a “fanatic” devotion to bridge.

Throughout the civil rights turmoil, Judge Tjoflat said, the judges remained steadfast in their belief that the law would prevail. “Johnson had a great faith in the American people. So did Tuttle, all these guys did. And in the end, their rulings were completely accepted. People don’t even talk about it today.”

Publicly, the judges were matter-of-fact about their role in defeating Jim Crow.

Tuttle told biographer Anne Emanuel that the civil rights disputes were “the easiest cases I ever decided. The constitutional rights were so compelling, and the wrongs were so enormous.”

Johnson said in a 1991 interview that his rulings were based on the Constitution, not any moral agenda. “As long as you think you are doing what's right, follow the law, and the facts require it, you have to do it,” he said. “If you are not willing to do it, get another job.”

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.